This page is also under construction. More to be added later. I maintain a bulletin board here on staging problems.

Definition: staging problems are practical considerations that a theatre company might address in a production. These problems1 could be created by many different factors, including, but not limited to,

- the physical circumstances of the production,

- the text,

- the audience, or

- the general culture surrounding the performances.

The first factor is the one that people might most commonly associate with the notion of a staging problem. For example, if a play has parts for fifteen characters, but the company has only twelve actors, then some doubling will be required. Depending on the maximum number of characters in a scene, the play is either doable or not.

Other examples could be the layout of the stage. In a famous anecdote, Sondheim waited until he knew how many steps would be in a staircase on the set of Follies before he wrote music that accompanied an actress when she ascended and descended the stairs.

The text could create staging problems. Henry V, for example, is one of the few Shakespeare plays that has significant stretches of dialog in French between Henry V and Catherine. Since Catherine is a native speaker of French, therefore, the character needs to be played by someone who can speak French with a reasonable accent.

The audience could also be the source of a staging problem. If the audience, for example, is more used to films and is less used to the types of artifice in theatre, that can pose a challenging situation for a theatre company and might determine what sort of plays it produces.

The fourth factor of the overall culture surrounding a show extends the notion of an audience beyond the specific people in that theatre for that one particular performance. It has to do with the context in which that production sits.

I’ve discussed each of these factors in isolation, but, of course, what I’m really interested in are those situations in which two or more factors contribute to a staging problem.

The example I cited on the home page about the disparity between the demographics of Shakespeare’s characters and of the audience is a clear case of both the text and the audience contributing to a staging problem through their interaction. Each factor on its own doesn’t necessarily produce that staging problem. You can look at the fact that only 16 percent of characters in Shakespeare are female (and only 17 percent of the text is spoken by female characters) by itself. It may or may not create a staging problem. However, once you start to incorporate other factors, such as whether you can staff the production (e.g., will there be enough actors to play all the roles) or what the concerns of the audience are, then you potentially have a staging problem. This is a specific case of a more general staging problem, which is:

Prob 1: how can you produce a play so that it articulates interests and concerns of an audience that is likely to see it?

This is related to but slightly different from:

Prob 2: how do we express important attributes of a play in cultural terms that the audience knows well?

The first deals more with things that an audience knows it might specifically want. The second deals more with a feel and what the audience knows or feels comfortable with. Both are cases of:

Prob 3: how do we meet the audience halfway?

and

Prob 4: how do we know who our audience is? How do we have an in-depth knowledge of that audience and not a superficial or perfunctory one? What happens if we don’t?

This may seem like a tangent (and it is), but it’s also related. Let’s see what often happens in another art form.

It’s a commonplace, almost a cliche, to hear jazz musicians complaining that no one listens to their music. Oftentimes, this is combined with some remark that so-and-so pop musician, who doesn’t have as much technical skill, has an audience of millions. It’s true that the audience for jazz is tiny, but a lot of the details behind this situation often aren’t acknowledged by its practitioners. As a performing art, jazz (or any other music) exists on a two-way street in which the audience and the musicians are supposed to listen to each other. The audience listens to the jazz musicians. That’s the obvious part, but the part that isn’t quite so obvious is whether the musicians listen at all to the audience, and by that listening, I mean that the musicians know in detail what the audience listens to, likes, and prefers. For bonus points, you can identify other things about the audience that may be extra-musical.

It didn’t use to be this way. From the 1920s to at least the 1940s, jazz musicians had a fairly good idea what their audiences listened to so their repertoire and the way they created solos was in alignment with that. I don’t think that’s the case now. Part of this has to do with the decline of the Great American Songbook, which, while it lasted, created a common space for the audience and musicians to communicate, but part of it goes beyond a repertoire. It has to do with an attitude towards the audience and of ignoring it except when it comes to collecting money for services rendered.

In comparison, a lot of pop musicians spend a lot of time researching who their audiences are. You have explicit examples like the Grateful Dead that took polls of its audience, asking them what tracks they liked when an album was being recorded. Taylor Swift may appear to be totally different stylistically, but her approach is very similar. She knows what her audience is and what their interests are in minute detail, and that’s not just musical interests. Meanwhile, most jazz musicians know what their colleagues’ interests are, but that’s not the same thing, and the audience knows it’s not being listened to. Whether or not they can overtly identify that they are not being listened to is not the point. A lot of what happens happens subconsciously, and when the audience senses that the practitioners are not listening to them, what they usually do is stop listening, themselves. After a while, they stop showing up.

Obviously, I’m not just talking about jazz here. You could make similar arguments about a lot of contemporary classical music in which the composer is listening, if at all, primarily to other colleagues, often those who are going to be determining tenure. That’s a fundamentally different act from listening to the audience. On the simplest level, when a composer writes for an audience that will experience the piece in real time, everything needs to be communicated in the sound of the work. When a composer writes for colleagues, then that’s not the case. In fact, if the work is being judged by its score, how it looks on the page and how it can be analyzed as a written work can take precedence. That’s not, by any means, the same standard as insisting that the auditory experience is everything. I’m digressing, though.

The main concept is keeping a close eye on a specific audience, and that’s a tricky matter.

The home page has eleven examples of staging problems. I’ll be posting some in the near future. Many of them are linked to specific musical settings. Most musical settings are answers to specific staging problems.

This might also be a good time to reach out to you as you visit this website.

If there are staging problems in Shakespeare that you find interesting and/or tricky, send them along. Use the contact page. I’m particularly curious about staging problems that came about in an actual production, but that’s not a prerequisite.

To illustrate how wide this category is of staging problems, here’s an example of what may be the most pervasive staging problem of them all:

Prob. 5: how do you avoid getting into too much debt when you produce a show?

Prob. 6: How does a production deal with characters in Shakespeare who have severe flaws but who get rewarded by the end of play? (Examples: Claudio in Much Ado about Nothing, Proteus in Two Gentlemen of Verona, Bertrand in All’s Well that Ends Well, Leontes in A Winter’s Tale.)

Does a production try to get the audience to sympathize with the character or just let the cards fall where they may?

1. Note that the use of the term problem doesn’t a negative matter nor does it mean that we have to have a solution in the production. It means that the problem is well-defined. It may have any number of possible solutions. In some cases, it is clear that the problem either can or cannot be solved. In other cases, this isn’t clear at all.

Henry V (liner notes and some staging problems)

These notes are patchwork. They’re not meant to form a unified argument but rather to lead a specific discussion on staging problems in the play. I’m leaving them here for a while, though, even though they are tangential to the main topic of using musical settings to solve staging problems because they illustrate some possible early steps to create musical settings: first identify the main staging problem; then figure out how to solve that. It may turn out, in this instance or others, that the best solution is not through music. That’s fine. The point is to be somewhat intentional with whatever music is composed. It needn’t always solve a problem, but if it never does, then it threatens to become wallpaper.

Opening question:

Tranquila prima; turbulenta ultima.

or

Turbulenta prima; tranquila ultima.

Prob 1: does a production portray the lead character as admirable or not?

This is a paraphrase of the central question in Emma Smith’s lecture on the play, which asks whether Henry V is admirable? That leads naturally to the staging problem above, how does a production portray the monarch?

Smith continues that there is plenty of material to support either case. She also claims that the good and bad sides of Henry V are so difficult to reconcile that a reader or audience member has to choose either a positive or negative view of the character. That, I’m not so sure of. I think that a portrayal could exist anywhere on the spectrum from bad to good, but we can get to that later.

One obvious task to do is list all of Henry V’s positive and negative traits. There is plenty on both sides. Note that in some instances, the positive and negative traits are very closely linked together. The staging question that a production needs to face is what text (and therefore, what traits) to support or suppress to in order to advance a certain characterization of Henry V. That raises an obvious staging subproblem.

Prob 2: if a production does not take sides, i.e., gives a neutral or flat reading, how much of the audience is going to be confused? Is that a bad thing?

You always have the default option of a flat reading, i.e., a plain recitation in which the speaker just focuses on getting through the words, which is often what happens in the first rehearsal or first run-through of the text. If you persist in this, will it cause problems for the audience?

Here are some questions and remarks related to what sort of spin a production wants to put on this character.

Ques: Is Henry V a tragedy or comedy? That depends, of course, on what your definition of tragedies and comedies are.

Historical question: what was Henry V’s reputation in England in 1600?

This is not just a historical question, by the way. If we have some idea, then we might know what the original production was working with or against. That could give us insights into how to produce this play now. That also has a related question: is this play really about Henry V, or is it about some aspect of politics in 1599? Is Olivier’s 1944 production about the 1410s or is it about something else? Ditto, Branaugh’s 1989 production.

Ques: Why have some productions tried to portray Henry V as overwhelmingly admirable? Historical contexts? Religious contexts? Examples?

Note: Chorus’s prologue to Act 2:

Now all the youth of England are on fire,

And silken dalliance in the wardrobe lies;

Now thrive the armorers, and honor’s thought

Reigns solely in the breast of every man.

They sell the pasture now to buy the horse,

Following the mirror of all Christian kings

Ques: is the last phrase positive or negative?

Note: Chorus isn’t in the quarto edition, only in the Folio. (Questions about traditional role of chorus in Greek tragedy. Also compare to role of chorus in pop songs.)

Prob 3: does a production use the quarto or the Folio version. Almost all productions use the Folio.

Quarto here at https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/H5_Q1/complete/index.html

Folger here at https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/henry-v/read/

Here’s Chorus’ epilogue:

Thus far with rough and all-unable pen

Our bending author hath pursued the story,

In little room confining mighty men,

Mangling by starts the full course of their glory.

5 Small time, but in that small most greatly lived

This star of England. Fortune made his sword,

By which the world’s best garden he achieved

And of it left his son imperial lord.

Henry the Sixth, in infant bands crowned King

10 Of France and England, did this king succeed,

Whose state so many had the managing

That they lost France and made his England bleed,

Which oft our stage hath shown. And for their sake,

In your fair minds let this acceptance take.

⌜He exits.⌝

Here’s Chorus’ prologue:

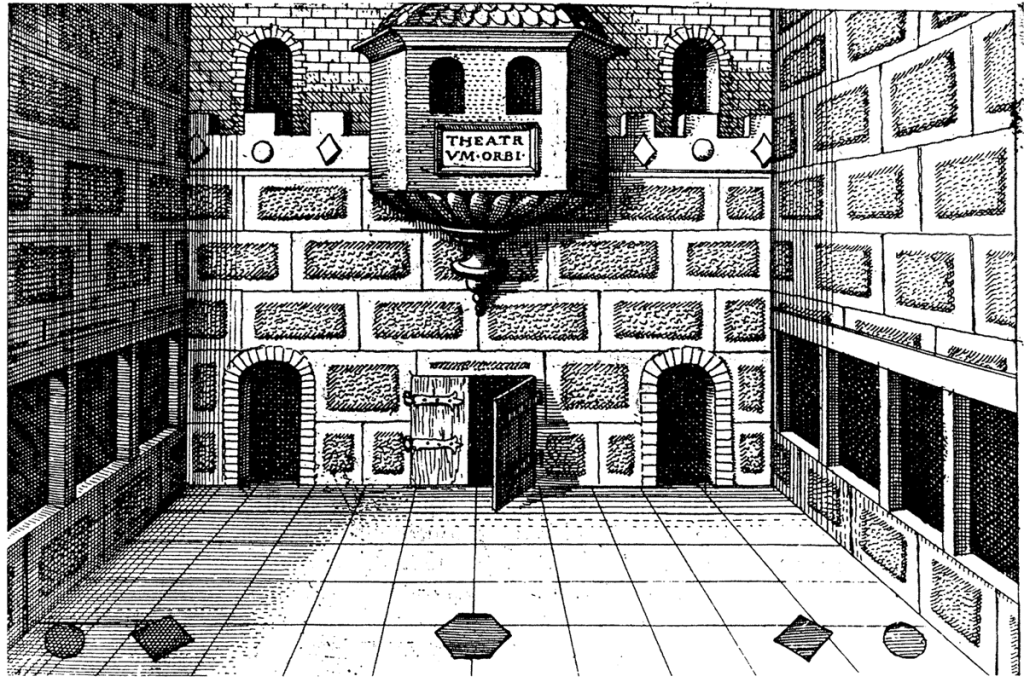

O, for a muse of fire that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention!

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and

fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon, since a crookèd figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high uprearèd and abutting frontsThe perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts.

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth,

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’ accomplishment of many years

Into an hourglass; for the which supply,

Admit me chorus to this history,

Who, prologue-like, your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge our play.

Here’s the prologue to Romeo and Juliet, just for comparison.

Two households, both alike in dignity

(In fair Verona, where we lay our scene),

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

5 From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-marked love

10 And the continuance of their parents’ rage,

Which, but their children’s end, naught could remove,

Is now the two hours’ traffic of our stage;

The which, if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Here’s the epilogue to A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

ROBIN

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this and all is mended:

That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme, 445 No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend.

If you pardon, we will mend.

And, as I am an honest Puck,

If we have unearnèd luck

450 Now to ’scape the serpent’s tongue,

We will make amends ere long.

Else the Puck a liar call.

So good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

455 And Robin shall restore amends.

Ques: for a modern audience, where should the prologue and epilogue of Henry V go?

Non-staging prob: My default lens on Shakespeare is in terms of staging problems that have a direct bearing on how the plays can be produced. Having said that, I do understand the appeal of issues that can’t be classified as staging problems, at least not on their surface. Here’s an example of one such problem. It’s something of a rabbit hole, and you can see how literary critics and historians would have fun with this.

Critics try to date the first performances of Henry V by a possible reference to Elizabeth I’s sending the Earl of Essex to put down Tyrone’s Rebellion in Ireland. Chorus claims that Henry V was welcomed back after his victory at Agincourt the way that Essex was supposedly going to be. See (5.Chorus.25-36).

How London doth pour out her citizens.

The Mayor and all his brethren in best sort,

Like to the senators of th’ antique Rome,

With the plebeians swarming at their heels,

Go forth and fetch their conqu’ring Caesar in—

30 As, by a lower but by loving likelihood

Were now the general of our gracious empress,

As in good time he may, from Ireland coming,

Bringing rebellion broachèd on his sword,

How many would the peaceful city quit

35 To welcome him! Much more, and much more

cause,

Did they this Harry.

The sticking point for me, though, is that Chorus doesn’t exist in the quarto versions. If that’s so, can we use it to make any claims about dating performances?

There’s a larger issue here, which is to what extent we can use earlier editions (i.e., the quartos) to document what the first performances were like. These are the sorts of claims that are made especially with respect to quartos of Hamlet. The claims are that the quartos are useful, even though the text may be pirated, misremembered, and mangled, because they can help us reconstruct the earliest performances.

My question here is if the first performances of Henry V did have Chorus, and the entire Chorus is deleted (and that’s a lot), how much can we use quartos to tell us anything about first performances?

Several more related questions

- What happened to Essex?

- Was some sort of censorship involved?

- Was Chorus originally supposed to be in Q1? What does the way that Q1 was printed suggest?

- How authoritative is the Folio?

- How are prologues and epilogues treated in other quartos and the Folio? What about Chorus?

- Compare to Romeo and Juliet. Can that play yield any insights?

- Is Chorus in Henry V uneven in quality?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of putting a chorus in a play? (Examples: Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Allegro. The Life and Times of Harvey Milk.)